I find myself once again in uncomfortable territory, grappling with how a former Supreme Court Justice’s report on the culture challenge facing the CAF has made me feel. In this case, I wasn’t angry with what the Arbour Report said, rather, I’m sad by what is being said or done about it on various social media platforms. It’s tough in a few characters to articulate that feeling. I share this article instead.

Words must become action

This article, “We Must Do Better,” is really a book review in disguise.

Daniel Coyle’s The Culture Code was a powerful read that highlights what you can get when you give a little. It outlines what can happen when you send the right signals to other members of your team, setting aside dated and flawed ideas of what it means to be a leader in the military. Vulnerability is not a weakness, it is a strength. Dissent, challenge and disagreement need not equate to disfunction, disloyalty, or insubordination. Quite the contrary, it can be a signal that there is trust.

Trust is one of the most important components of any team. Words do not build it, but words can erode it. Actions can work both ways, another reason why our actions, our behaviours, matter so significantly.

“It Wasn’t That Bad” – A Bar Set Too Low

“It wasn’t that bad.” I said those words frequently. I meant them honestly.

I have heard so many people say that phrase. And while the light was starting to come on for me on my “Rocky Road to Self-Awareness“, it crashed into me during an interview with a soldier in early April when they were sharing with me a story of inappropriate and harmful behaviour.

The soldier said, “It wasn’t that bad, nothing physically happened.”

It was a gut punch. I could have cried for having felt like such a failure, for having said that phrase far too many times in the past. It allowed things to stay the same. To have my words parroted back at me by someone 20 years my junior showed me just what I taught people anytime I said it myself. As much as I feel like I may have lacked the personal power to speak up when I was one of the early pioneers of women in the combat arms, that’s a bullshit excuse to which I will no longer allow myself to subscribe. Because guess what? That excuse won’t ever go away. When does a victim or a more junior person ever feel like they have power?

Why did I ever think that “not that bad” was the standard we were trying to achieve? “Not that bad” is a bar set too low folks. We can do better, we must do better.

My advice to anyone when they hear someone describing a situation of behaviour especially, and the situation is qualified with, “It wasn’t that bad,” is to treat it like a stoppage on a weapon. Your immediate action ought to be the equivalent of canting your weapon to the left to investigate the position of the bolt. Dig a little deeper into that situation, investigate it more. Because if something wasn’t that bad, it also wasn’t that good. Perhaps a better question is whether it was acceptable, or unacceptable. Thinking in those binary terms removes the middle ground of “not that bad,” middle ground that is code for unacceptable behaviour in far too many instances.

Let’s raise the bar, collectively. Demand it of each other.

To be (the contrarian), or not to be…

I had a draft article sitting in my blog-o-sphere since early September that I never published. I was concerned about who might read it and what sort of trouble that might invite, either from higher or more importantly, lower in my chain of command. I hit publish this morning, regardless. Here’s the link, in case you’re interested: “When the outspoken go quiet.”

The number of emails or letters I have drafted and not sent, or formulated in my mind as I toss and turn before finally falling asleep, since September is ridiculous. There is so much I want to say, but I don’t know who will listen, nor how to deliver the message in a way that it will be credible. A contrary or challenging voice is fraught with risk, most especially in hierarchal structures such as I find myself a part of. Equally, there is risk to not voicing things as well – stagnation being but just one.

In my baby Twitter days (@jencauseyarmygirl_jen) I came across a recommendation for a book, Leadership on the Line by Ronald A. Heifetz and Marty Linsky. I’m less than 50 pages in and I think I have highlighted about 10 different sections thus far. A couple warrant mention here:

You appear dangerous to people when you question their values, beliefs, or habits of a lifetime. You place yourself on the line when you tell people what they need to hear rather than what they want to hear. Although you may see with clarity and passion a promising future of progress and gain, people will see with equal passion the losses you are asking them to sustain….

But, adaptive work creates risk, conflict, and instability because addressing the issues underlying adaptive problems may. involve upending deep and entrenched norms. Thus, leadership requires disturbing people – but at a rate they can absorb.

– Leadership on the Line, Ronald A. Heifetz and Marty Linsky

If not me, then who? Who will speak? Who will ask the questions that need to be asked?

I find the silence to be deafening, so I choose the path of contrarian. But I must learn how to navigate the path wisely, at an absorbable rate. Wish me luck friends.

The challenge of change

One of my earliest articles, “Leaving the Military Felt Like Divorce,” has a misleading title. I didn’t leave the military. I left the Regular Force, but remained a member of the Primary Reserve. I thought that with a different focus, service without aspirations of career advancement, only with the intentions of trying to provide some leadership and some horsepower to my unit, that I would feel rewarded and and could accept things I didn’t like about the Canadian Armed Forces.

It worked, for a brief stint. I love my unit. We are small, we are inclusive, we are committed. But alas, we cannot operate in a bubble, isolated from everything else. And I cannot seem to stop caring. I have been critiqued for caring too much, and for not being smart enough to pick my battles. I don’t accept that critique very well to be honest. We need people to care. We need people to fight for change, because folks, it is a fight. And I openly admit that I am running out of steam, again.

I read what the then Army Commander had to say about agility and change. Nothing has transpired in the last 5 years of my Reserve service to make me believe we (the CAF) is getting any better at change. LGen Eyre’s words are aspirational to be sure, and listening to him in his current appointment as Acting Chief of Defense Staff, I know he truly desires change. But forgive me, my cynicism, a product of my lived experiences, tells me it briefs a hell of a lot better than it does being put into practise. Click here to read my answer to “Agility and Change.”

The Rocky Road to Self-Awareness

Well folks, I am not gonna lie, it has been a rough ride as of late.

If you’ve read some of my other articles, this one specifically, you have heard me say that I resented the implications of Madame Deschamps Report on Sexual Misconduct within the Canadian Armed Forces because of how she categorized female senior leaders as blind to the problem, or for having developed some sort of coping mechanism.

The inner dissonance I now feel as I have to be prepared to chew on her words, and mine, is brutal. On one hand, I can say that women in the combat arms in the 1990s and early 2000s likely lacked the personal power to hold people to account. But that excuses my failure to speak up.

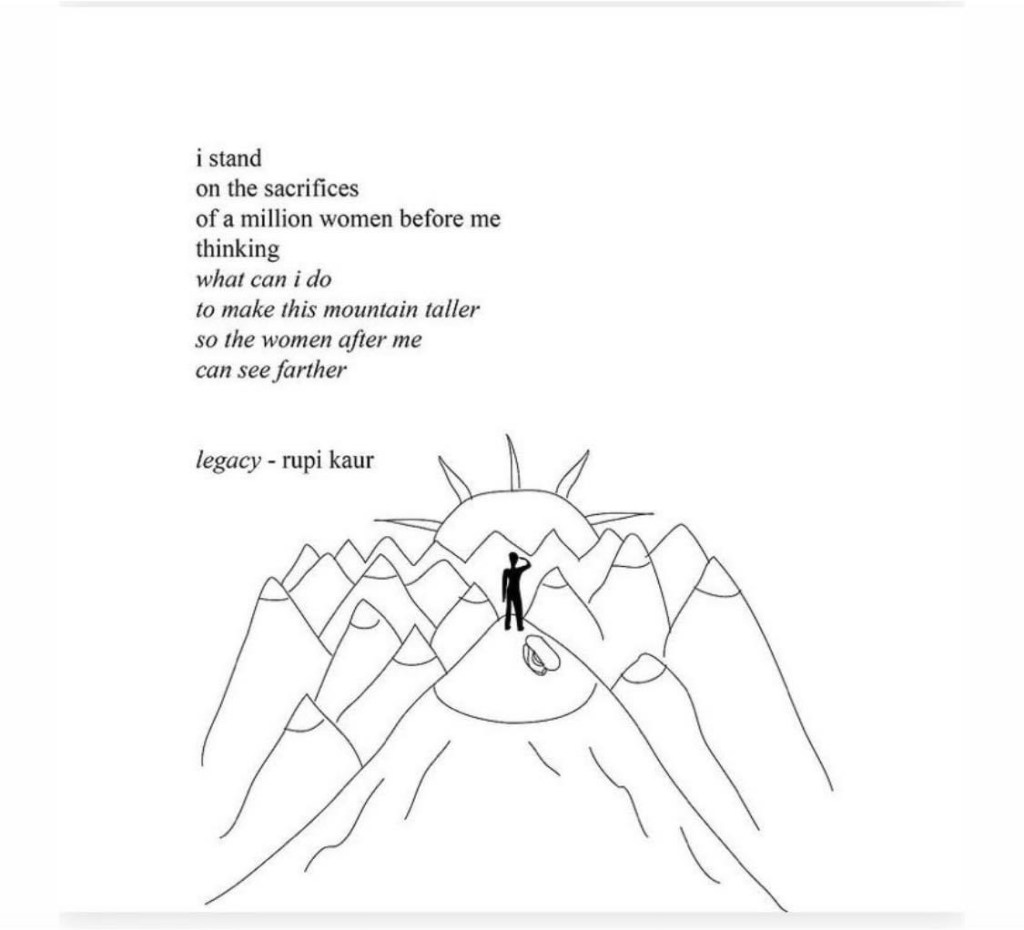

On International Women’s Day, someone had shared this in a mentoring network I am part of:

I am torn. I now wonder if when I picked my battles so I could win the war, as I talk about in this article, did I help build a taller mountain that was made of sand in the bottom?

I don’t know. It’s a crappy feeling all around. It’s difficult to be proud of one’s service when your faults are suddenly staring you in the face.

But then, where were the men in all of this? Where were the more slightly more senior leaders who ought to have been helping slay the dinosaurs? Why did it have to fall onto me to correct those small slights?

I know my peers were on my side and shared my views on some antiquated views. And I know that at times they did go to bat as well. But still, why as a whole did we not feel empowered to push harder?

I’ve been writing for my own cathartic purposes on topics related to current news headlines on allegations of misconduct or inappropriate relationships in the Canadian Armed Forces, but nothing has morphed or matured enough that I have been able to post. Today I had an exchange with a senior officer that inspired me to at least share this much. I feel a compunction to try to articulate what I’m working through and put it out there for consumption. This is a first start. More to come on my journey of talk-think-talking, or more accurately, write-read-writing.

Too little, too late….

During my Unit Command Team Course we had a briefing from the Commander of Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group. It’s an organization that as it’s name would suggest, caters to transitioning members, primarily from the Regular Force. As my course was for Primary Reserve Commanding Officers and Regimental Sergeant Majors, one of our primary concerns was how do we convince transitioning members of the Regular Force to continue to serve on a part time basis. Let’s face it, Regular or Reserve, attrition is our nemesis. But for the Primary Reserve, capturing that former regular soldier or officer who left because the demands of full time service were no longer compatible? That’s gold! That is magic. That is experience that we are hard pressed to match. I can’t recall the exact question that was phrased, but the Commander’s answer was that yes, first and foremost, if they can keep the member serving, that is the ideal. It stuck in my mind and gnawed at me. By the time the member reaches the point they are at the transition unit, any effort to keep them in uniform is probably too little or too late, in my opinion. Humour me….

Today, all transitioning members transition through this organization, however, it was borne primarily out of a purpose to service our ill an injured. It was a place that our ill and injured could go so that they could focus on their rehabilitation to either get healthy and return to the unit, or focus on their next bound into civilian life. From my limited perspective, in it’s infancy the return spring back to the unit was broken and this unit facilitated a transition out of the Canadian Armed Forces. I think that is changing, but that is an aside, and I’ve drifted off topic a little. But by the very name of the unit, perhaps I haven’t. Because by the time someone has arrived at the Transition Group, their mind is made up; they are either leaving by personal choice, or because they are no longer medically fit to serve. The role of the transition group shouldn’t be to change a soldier’s mind. Their job should be to facilitate transition. It got me thinking about my own experience, and that of some of my close friends, and it had me going back and revisiting some of my other articles. Specifically, the article “Career Advice I Wish I Had Got.“

Retention is a tough problem to tackle, but it is a very important one. For the purposes of this article, please bear in mind that I am talking about my perception of the challenges with career management of Regular Force officers in particular, and how that relates to retention. My perception may equally apply to non-commissioned members as well, but perhaps not. The above disclaimer is really my way of saying that I’m about to make some broad brush generalizations about things I feel are wrong, and how those things end up hurting the Forces in the long run because it loses talent it can ill afford to lose.

To be perfectly blunt, I think that the CAF takes a view that is myopic, a little too simple or shortsighted, and hasn’t acknowledged the change in demographics. Just a few examples of variations of career advice/management or snippets of conversations that I have experienced or witnessed or given (yes, I’m guilty too) over the years:

- Nobody joins the Army so they can be a staff officer in some cubicle in Ottawa, right?

- In the Artillery, the age old debate rages between those who are Instructors in Gunnery (IG), and those that are not, and which path is the “better” one and why. What do you mean you don’t want to do the IG Course? Gasp! Don’t you know it’ll get you 2 extra points on the merit board? You’ll be a better Battery Commander because you will be more technically and tactically competent.

- You want to go to a Recruiting Center, or a Reserve Unit as their Regular Force cadre? Ohhhh, big intake of breathe, maybe even the disappointed/concerned Dad face “Are you sure? They aren’t seen as A-jobs. You will be a little out of the loop. You’ll have to make sure you make an effort to stay in touch with your old unit.”

- You want to do Tech Staff? “Okay, that’s not a bad option. It’ll get you the extra points as well, and you’ll get your Masters. But you know you may get pigeon-holed into projects for the rest of your career?”

- Said with a little bit of anger, disappointment, or with the intent to lay down a healthy dose of guilt, “What do you mean you don’t want to accept job X? If you turn this down you might not ever get the chance again. We’re offering you this because we see potential in you!”

What’s the common thread in all of those above examples? Not a single one of them considers what the member actually wants, or what their career aspirations are, and nor do they make it seem like it is “safe” for the member to express their desires. They are almost all premised on the assumption of career progression aimed to promotion and appointment into command positions. We are often far too presumptuous, to the institution’s detriment.

How does one’s potential drastically diminish in an instant, just because they dared to say that the career path the institution saw them going on wasn’t the same one that they envisioned, for whatever reason? Who benefits from shaming them over their choices? Who benefits from blindly pushing them on a path they are not fulfilled by? Nobody.

I know it is incredibly difficult to manage the needs to the service with the needs of those that serve, so I do not envy the career managers in the least. They have a challenging job and will be unable to make everyone happy. I also acknowledge that when the time comes and the service does need you to go somewhere that might not have been your first, second, or even third choice, there are times when you really do need to just suck it up and go. What I’m talking about is the climate that surrounds the very topic of career management in general. Breeding loyalty, obedience, service before self all help create a culture where we never really learn a person’s true desire. That creates problems. That is not a relationship built upon trust.

I have had some fantastic support in my career when I had to make tough choices for personal and family reasons, and I am so very grateful for that. But the kind of support I was shown by two different Commanding Officers in keeping me on track to complete the Joint Command and Staff Course at a time and in the manner that most suited my needs, is too rare. I didn’t really have an exit interview when leaving the Regular Force. But funny enough, the Brigade Commander of the Brigade at the Garrison I was on at the time, an officer I had worked for in the past, but no longer worked for and wasn’t artillery, reached out to me when he heard the news and wanted me to come by for a chat. He prefaced it by saying that he wasn’t going to try to change my mind, but that he wanted to know why. He wanted to see what had transpired and where my head space was. That small token of his time, and a realization that he wasn’t going to change my mind, meant the world to me. But imagine the difference it would have made had my own chain of command bothered to listen to me, to really have a conversation about my future six months prior? That it didn’t happen led to my article, “The Truth May hurt, But Lack of Honesty can be More Harmful.” As arrogant as this may sound, the Canadian Armed Forces is lucky they didn’t lose me outright. I opted to stay for part time service, but I could have walked completely. And are they really wanting a person of 23 years experience to walk?

You become an officer because you want to lead, but leadership can exist in many forms. Very quickly however, you are pressured/brainwashed into believing that you should want to command. I was a staff officer in a cubicle in Toronto. It wasn’t necessarily my dream job, or what I specifically was trained to do as an artillery officer, but I had a section of officers and non commissioned members who work for me. They needed some leadership, just as much as anyone else in uniform. Why are we made to feel “less-than” because we are leading in a different environment? I had at one point wanted to be in recruiting, but I was made to feel that that would have been career suicide. Are we really that immature as an institution? My fear, and why I am writing this article, is that I think the answer is yes. I hope that it has changed since I left the Regular Force, but I fear it hasn’t.

Other military forces subscribe to the up or out philosophy, by policy. We do not, and nor should we, in my opinion. But nevertheless, we have a culture that is very closely aligned with it and I think it is to our (the CAF’s) detriment. Waiting until someone is sitting in front of you, telling you they need to release is too late for you to act concerned and ask what it is they really want to do, or why they are not satisfied. It is not the time to start bending over backwards, trying to appease someone and keep them in uniform. That is an afterthought, and nobody wants to be an afterthought. An afterthought is too little, too late. We owe our people more than that. If we value them as we say we do, if we value diversity as we say we do, then we should allow people the safe space to articulate what it is they want from their career without the fear that they are hammering a nail in their career coffin.

Transition is not the time to change a person’s mind. It is a time to wish them well, to set them up for success. Send them to their next destination with the hope that you have prepped them well, and someone else will reap the benefit of your efforts in training this person, and that will reflect positively upon the institution. Sometimes, transition is just because it was never a good fit. Sometimes, it is because of a physical or medical limitation. Sometimes, it is a cultural issue. Whatever the root cause, it should invite the institution to reflect and see where they can change. That I have yet to have been briefed in my 26 years of combined service on the attrition statistics speaks volumes to me. I am not bitter, but I am disappointed. We owe our people more than that. We owe them a safe space to have a conversation about their career aspirations, whatever they may be, without fear of repercussion. They are not an afterthought. Instead of too little, too late, let’s engage early and often with a view of doing a better job of striking the balance between the needs of the service and the needs of the member. I think that is a crucial part of leadership.

A Lifelong Education

I swore an oath to serve my country 26 years ago today, at the young age of 17. A few days later I crossed the country from one coast to the country to the other to begin my Basic Officer Training. I have such a distinct memory of sitting on the plane listening to music, with my two fellow Newfie recruits, and it was Blue Rodeo’s “Hasn’t Hit Me Yet.” The song is about something entirely different, but that line specifically resonated, and we all looked at each other and chuckled. It was about to hit us, about 24hrs later when we arrived at Canadian Forces Officer Candidate School in Chilliwack, British Columbia.

While it wasn’t a stretch for me to end up in the military, it wasn’t something I had a dream of doing. I knew about the Regular Officer Training Program (ROTP), and the Royal Military College, because my brother had signed up five years ahead of me. But to me, all it really represented was a free education. It was a way to get my degree paid for, with a guaranteed job at the end of it, I would be bilingual, and I would only have a minimum five year commitment upon graduation. There was also an escape clause; up until the first day of classes in your second year, you could opt out and owe nothing. Seemed to me that it was a great way to avoid a massive amount of student debt.

I picked up the application, but never followed through with submission. In fact, I had already accepted my offer from ST FX in Antigonish, Nova Scotia when the recruiter called me to follow up on my application. I had assumed I was too late by then. He told me to bring it with him when I came for an interview. So off I went. I recall the interview ended up being a lengthy discussion on my involvement with sports, and he asked me if I knew where any of the bases were located in Canada. To this day, that job interview is my one and only successful job interview, because when the offer came, the free education trumped the small entrance scholarship I had to St FX. And here we are still, 26 years later, all because I didn’t want to have student loans.

By a free education, I was simply referring to my Bachelor’s degree. That’s all I was really looking to get out of it. I can tell you though, that “free” education felt anything but free during my summer training in Gagetown, New Brunswick. I think on our week long defensive exercise in the summer of 1996 us ROTP Officer Cadets calculated what our salary equated to for an hourly wage, and it was less than $2/hour! When I look back on it now however, that Bachelors degree I was in search of for free was just a small drop in the bucket of lifelong learning that my career afforded me. My work anniversary has given me cause to reflect upon the lifelong education my career has provided.

I may not have a degree in sociology, but I have had 26 years of learning about people – their interactions, how they react when challenged, and conversely how they behave when they have idle time on their hands. I have seen team dynamics in play in a variety of settings – large group, small group, homogeneous, and diverse. I have bore witness to a multitude of different leadership styles, and been challenged by a wide range of followers or subordinates – the overachiever, the self-doubter, the cocky, to just the average soldier who wants to do their job well. I have seen them celebrate successes, and I have seen them grieve in times of loss. I have shared in some of those moments.

I have learned to be flexible and adaptable. While the military has taught me formal planning processes, the expressions “plan early, plan twice,” or “why plan when you can react” are used frequently enough in a somewhat joking manner, but based in reality because the situation often changes. Plans rarely survive contact, meaning all bets are off once you cross the line of departure. If you cannot react to change in the military, you are destined for failure.

Je suis capable de parler dans les deux langues officielles du Canada, not perfectly, but I can get by. Moreso, I have learned about communication in the broader context. I have learned the importance of timely and appropriate feedback on performance, whether it be positive or negative. I have had to deliver tough messages, bad news, and had to have uncomfortable conversations. I have had to rely on written communication to advocate for my soldiers (or myself), or to administer them out of the Canadian Armed Forces when it was necessary.

I have learned about accountability, authority, and responsibility, and how there must be an appropriate correlation between the three to be effective in your position. I have sometimes learned lessons about responsibility the hard way, where it was difficult for my perfectionist self to accept. Things will happen that are beyond your control, or direct influence, but as the leader you are ultimately responsible, and yes, sometimes that sucks.

I have had to undergo formal training throughout my entire career, with my most recent course having just been completed last week, the Unit Command Team Course. While my basic officer training, and my specific occupational training, all served to introduce and teach new skill sets that were necessary for me to do my job, the benefit of some of my other training was not in the new material being taught. In fact, I would be hard pressed to put my finger on new information or skills that either the Army Operations Course, the gateway to promotion to major that all Army captains take, or my Joint Command and Staff Programme, the gateway to Lieutenant-Colonel, taught me. By the time you arrive on those courses, depending on your background, what is being presented isn’t necessarily new or unfamiliar, but the value is in the opportunity to practise and exercise certain things in a learning environment with a cross section of officers from the Army or the Canadian Armed Forces. It is in the informal discussions and debates that arise in the conduct or in the margins of the course. The value is the connections that you make that will carry on throughout your career. From my perspective, the greater value of those courses are in the people with whom you attend and the professional relationships that are borne from it.

A career in the Canadian Armed Forces is a dynamic one that revolves around people. And being around people is always going to teach you something, whether you realize it or not. What I mention above is only a small snippet of the things I have learned in the past 26 years. The free education I signed up for turned out to be the gift that keeps on giving. It has given me a lifelong education.

A lot of thinking, not a lot of writing…

Hi folks, it’s been a really long time. You know how it goes, life gets busy and you lose your muse. That was me, until recently. Between the current events with protests in the USA, #BlackLivesMatter, and reconnecting with my university friends and having some deep discussion about our experiences in the military, I find that I’m looking inward more than I have of late. I need to chew on it, and I need to figure out if I actually have anything new to say, but it has caused me to circle back to an article I wrote in October of 2018, “Why Meritocracy is a False Ideal.” I was prompted to share it after viewing what General Charles Brown of the United States Air Force had to say.

Over the course of the past several weeks, many of my military friends have posted on Facebook a short paragraph about how they don’t see colour, they only see the uniform. I didn’t comment on any of those, but there was something about their particular post that nagged at the back of my mind. Listening to General Brown helped me get a grip on what it was exactly, and it sort of ties back (not entirely) to the what I allude to in my 2018 article that I have just added to this blog. But it’s deeper than that.

When my colleagues and friends were posting about not seeing colour, I do believe that their sentiment was well intended, but …. it somewhat misses the point.

I’m guilty of it myself. When asked about being one of the only or few women, especially in the early days, I often reply by saying that for the most part, folks in the military don’t care as long as you can do you job. There is a great deal of truth in that statement, but the statement in isolation does not give the full picture. It doesn’t acknowledge the pressure, feeling like you are living in two worlds at times. The lived experiences of the minority are very different than the lived experiences of the majority. I think you have to make an effort to see colour in order to begin to understand how deep and pervasive unconscious racism can be, let alone overt racism, especially when it isn’t your lived experience. There isn’t a quick and easy fix to racism or any other issue that is tightly woven into society over the course of history, but I do believe that it has to begin with a willingness to listen, to have tough conversations, to learn and overcome ignorance on the depth of the problem. So take a listen to this General Brown please. You can opt to read my article if you like, but his words are far more impactful, and relevant.

The outrageous-ness of moral outrage…

I had been relatively quiet in the virtual world the last little bit, partly because I was legitimately busy. I had recently been promoted and appointed as the Commanding Officer of 42nd Field Regiment (Lanark & Renfrew Scottish), RCA. But that wasn’t the only reason. There was a much more significant reason, a personal one.

I’m still processing and trying to decide how I feel. As I was working my way through that internal churn, I finally reached a place where I could write. I produced an article titled “Black, White, or Shades of Grey,” but I have been sitting on it for about two weeks. I wasn’t ready to put it out there. And then Don Cherry happened.

I am so tired of moral outrage. I am tired of people not being able to see the spirit of the message. I am tired of hypocrisy. I look at the contrast between the reaction to Don Cherry, his choice of words, and the fallout and out-cry from a nation, to that of what happened on Survivor two weeks ago. Contestant Jack uses the term “durag” when asking contestant Jamal to move a pot of rice. Jamal was offended. But what followed was an example of maturity, grace, and healthy discussion. Can we say the same about Don Cherry’s use of “you people?”

I don’t even want to join the debate on it. I have seen several posts or articles whereby people comment from a very neutral position, and I appreciate those very much. An opinion piece by Jessica Swietoniowski, “A response to Don Cherry’s firing from a daughter of immigrants” on The Post Millennial caught my eye, or one sentence in particular resonated with me, “Political correctness and cancel culture have taken leaps forward while moving us, a free society, backwards.”

Suffice to say, it was time to share my article. My personal debate or turmoil over not taking a hard stance on things where others have has ended, especially after this past week. I’m a good person. I try to see the good in people, to see the message intended vice focus on the specific words, even though words do matter immensely. I used to use words and turns of phrases that I now know are inappropriate. But I did so ignorantly and innocently. In a world of glass houses we as a society seem to be pretty quick to pick up a stone and launch it. I think I’d rather hang out in the grey, and keep trying to muddle my way through common understanding.